The article goes on to say that William Dockstader, owner of the theater, “was so impressed with the ability and popularity of the child that he offered an extra $10 for his services if the parents would permit him to appear in evening shows as well as in matinees.”

“‘The boy has a future.’ That’s what everyone said in those days, but they didn’t know that the future really meant stardom in the movies and legitimate theater. ”

— George Shtofman, The Journal Every Evening, Wilmington, Delaware, August 9, 1941

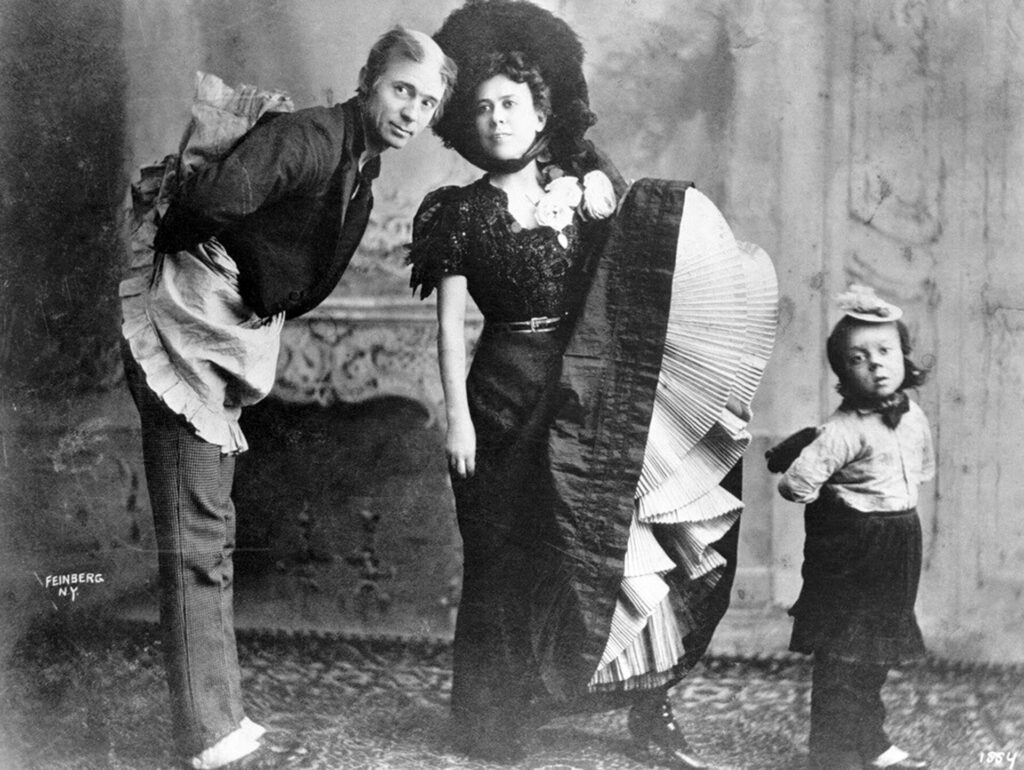

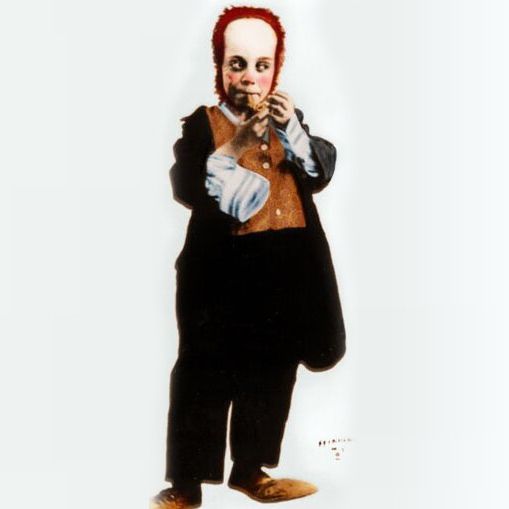

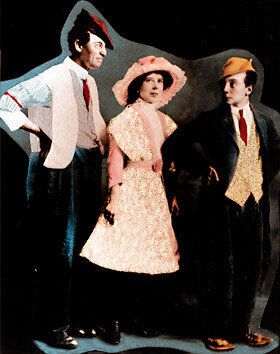

Beginning with that auspicious debut at the age of just barely five, Buster Keaton was a star, a big star. He toured the United States with his father and mother, performing their ever-changing act for 17 years, an act that generally started with Joe Keaton explaining to the audience how one should bring up a child while Buster behind him was wreaking havoc. The act constantly varied, providing young Buster the opportunity to sharpen his mind with improvisation and develop his gift for parody.

“Probably the biggest hit of the entire show was scored by BUSTER KEATON, a juvenile comedian of wonderful ability.”

— Boston Herald, January 16, 1904

The big laughing hit of the programme was made by Joe, Myra and little “Buster” Keaton. It is seldom that such hearty laughter is heard in a theatre as that which greeted the efforts of “Buster,” who is an exceptionally clever lad. Every word and action set the house in a roar, and his imitations of Dan Daly, James Russell, and Sager Midgely brought him to much applause that it is a wonder his little head is not turned completely around. “Buster” does not give the impression of having been taught; his work is so spontaneous and so accurate that it shows him to be above the average performer of his age in intelligence and indicates that he understands the value of pause and emphasis as well or better than many a performer of mature years. Joe and Myra Keaton also did excellent work. ”

— New York Dramatic Mirror, January 30, 1904

“Buster . . . is thrown about the stage by a merciless father in a careless fashion and his treatment and comedy are the things that bring the laughs.”

— New York Telegraph, January 1909

“The dexterity or expertness with which Joe Keaton handles ‘Buster’ is almost beyond belief of studied ‘business.’ The boy accomplishes everything attempted naturally, taking a dive into the backdrop that almost any comedy acrobat of more mature years could watch with profit.”

— Variety, March 12, 1910

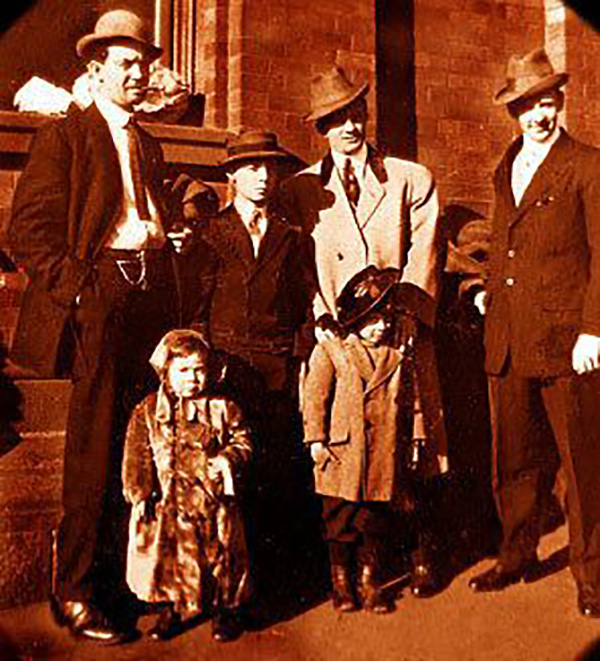

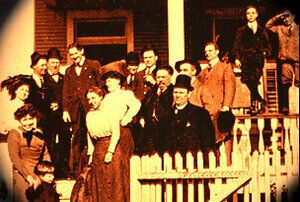

For young Buster, standing in the wings watching all the other acts, it was a priceless opportunity to absorb what American theater of the time had to offer. The solemn, big-eyed child made lifelong friends, mostly adults, during the 17 years he, Joe, Myra, and eventually little brother Harry (“Jingles”) and sister Louise traveled the vaudeville circuit and mingled with the best entertainers in the country.

On the road, Buster learned not only to be his father’s roughhouse partner, but to sing, dance, play the piano and the ukulele, juggle, do magic and write gags and parody. The performers he knew were also his teachers: Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, then at the start of his career, taught the little boy to dance, decades before he taught another child, Shirley Temple, to dance for the movies. The great Harry Houdini taught him card tricks. Buster, like the rest of the world, was enthralled with Houdini’s act, often watching him from the wings or even from up above in the flies to try to figure out Houdini’s secrets.

In his films Buster Keaton would often evoke these childhood theatrical memories, either with references to the theater of his youth or by making use of the varied skills he learned as a child.

Although Keaton would one day be praised for his brilliance, he attended less than one day of public school, in Jersey City, New Jersey, just across the Hudson River from Manhattan. His formal education ended abruptly at lunch time, after his quick wit and vaudeville gags proved too distracting to the other students and particularly to their teacher. His mother, who herself had only a third-grade education, taught him what she knew, eventually hiring tutors and governesses to fill in the gaps—at least that’s what the newspaper clippings claimed. But Keaton wasn’t learning from books, even with the tutors. He was learning show business. Of course, many vaudevillians had little or no formal schooling; Buster was not unique in this, even if he was unique in his talent.

Until Buster came along, the family act had not been terribly successful. In fact, during the week of Buster’s professional debut in Wilmington, the act was repeatedly and mistakenly advertised as “Mr. and Mrs. Joe Keating: The Peers of Break-neck Oddities.” After Buster formally toddled into show business and became a star, errors of this kind would not happen again. As soon as tiny Buster joined the act, the family fortunes improved. Where The Two Keatons had struggled, The Three Keatons were a hit. The serious little boy who liked getting tossed around on stage received enough public attention that it was in his parents’ best interest to keep him out there in front of the audience.

But it was difficult to keep him onstage. Joe and Myra were constantly asked to defend their treatment of their son in what seemed to be a brutal stage act. Buster remembered: “It was Sarah Bernhardt who said, ‘How can you do this to this poor boy?’ when they were throwing me around madly. Everybody said that.” The Gerry Society was vigilant on behalf of working children and so were local police. A half-hearted though somewhat successful attempt was made to pass Buster off as a midget in order to make the Gerries think he was an adult—and therefore not in their jurisdiction.

At other times, his parents were arrested because police were convinced Buster was being mistreated. “We used to get arrested every other week—that is, the old man would get arrested,” Buster said. “Once they took me to the mayor of New York City, into his private office, with the city physicians . . . and they stripped me to examine me for broken bones and bruises. Finding none, the mayor gave me permission to work. The next time it happened, the following year, they sent me to Albany, to the governor of the state.”